This story is a repost.

In his review in the New York Times today, Michael Kinsley calls Page One, the documentary about the New York Times, “a mess.” He’s right, but not in the way he thinks it is.

This is a movie about the news industry: of course it’s messy. Director Andrew Rossi leads his audience across the wasted media landscape, with stops along the way, writes Kinsley, at “WikiLeaks; the Pentagon Papers; more WikiLeaks; the survival issue; Gay Talese and his famous book on The Times, ‘The Kingdom and the Power;’ Comcast’s purchase of NBC Universal; the impact of Twitter; the danger of not sending reporters on trips with the president; how ABC has had to lay off 400 people.”

This is a movie about the news industry: of course it’s messy. Director Andrew Rossi leads his audience across the wasted media landscape, with stops along the way, writes Kinsley, at “WikiLeaks; the Pentagon Papers; more WikiLeaks; the survival issue; Gay Talese and his famous book on The Times, ‘The Kingdom and the Power;’ Comcast’s purchase of NBC Universal; the impact of Twitter; the danger of not sending reporters on trips with the president; how ABC has had to lay off 400 people.”

Apart from the messiness of the topic itself, there’s something nice about a sprawling approach, especially when our stories so often come in the form of Tweets, updates and headlines designed to be clicked on. It’s satisfying to see a fly-on-the-wall account of the business (and one of its epicenters) at a moment when transparency is king, but it’s also nice to be reminded about how good stories can be told. It can be hard to remember in the chaotic ecology of the Internet, where we follow links down their rabbit holes towards not wisdom, not opinion, not reporting – but information that’s crowd-sourced, aggregated, liked, and thus given a stamp of “relevant,” “important.”

By Kinsley’s account, the movie, with its impressionistic, rambling portrait of the news business, sounds a lot like the Internet too, born of a style that “keeps things moving but requires some discipline.” Discipline is what serious journalism has, and this, he’s clear, is not it: “It flits from topic to topic, character to character, explaining almost nothing.”

But the movie is a portrait of chaos, and a compelling one at that. It’s not a newspaper article or a well-structured op-ed. It’s a testament to the sort of journalism that still matters, that still separates Page One from the Internet’s homepages. It’s proof that in whatever medium you’re working – and there are a lot to choose from now – stories matter, and so do their sources and their subtleties. “Page One” may explain almost nothing, but some things aren’t so easily explained. Some times they have to be seen, and thought about, and discussed.

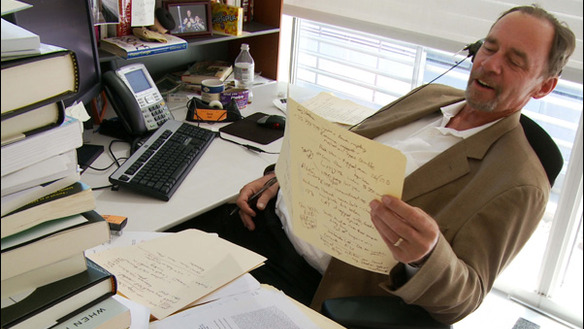

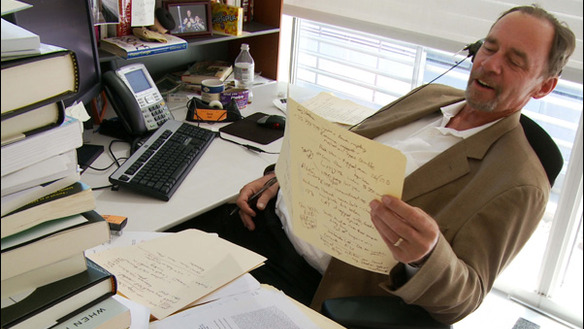

Kinsley’s bitter assessment then serves as proof of precisely the kind of journalism that the movie documents. In the interest of avoiding a “conflict of interest,” here’s the Times striving for as much distance as it can on a documentary about its own newsroom. Kinsley (who works for Bloomberg) goes out of his way at the start to indicate there is no conflict here, which was presumably why he was asked to write it (despite not being a film critic at all) and why he sounds nearly indignant at the film’s emphasis on “a media columnist and reporter named David Carr,” who is guilty, apparently, of loving the Times.

Given all of its (defensive) sense of self-importance – one stoked now more than ever, by, for instance, what some indignant Times partisans in the movie call “stupid” rumors of the newspaper’s demise – it’s not surprising to see a writer in the Times flaunting the paper’s concerns over integrity, like the righteous golden boy that new media expects it to be. “The Times deserves a better movie,” writes Kinsey imperiously, before adding the exortation, “and so do you. See ‘His Girl Friday’ again.”

Nerves have been touched clearly, and Kinsley’s review is only further proof, again, of a point that the movie is trying to make: if it’s not fighting for its life, good, level-headed journalism is on a mission to prove itself worthy in the heady, loud age of the Internet.

Carr is a fantastic spokesperson for that mission (and for the paper in general) and for the meta concerns at the heart of a shrinking newsroom. “There was just this sort of decades of organizational hubris about, you know, our own excellence and our own dominance,” he tells the camera early on in the film. “And then in a matter of like 18 months, all of a sudden…everybody started like asking a question: could The New York Times, like, go out of business?”

In an effort to remain balanced and fair and critical, papers like the Times aren’t competing against a “new media” boogeyman. They’re already deeply and often smartly embedded in the Internet themselves, and that’s where things get messy. Struggling with new modes of reporting, Internet economics and increasingly fuzzy lines between the demands of advertising and the demands of editorial, the corporate structure of news – “the muscles of the institution,” as Carr calls them – presents its own challenges to the newsroom. Through the collapse of the Tribune company and the Comcast NBC merger, the film points at these challenges, without making any claims. The story is still developing, is the point, and it’s complicated.

If “Page One” is ultimately a meditation on a shift between old and new technologies (Twitter and the iPad both make prominent, almost ominous appearances), what’s mostly missing is the story about the message that those technologies carry. When the tools effect the content, they’re really inseparable. But the content – what goes on Page One – gets little screen time here.

Still, in one of the film’s best scenes, when Times’ editors argue over whether to cover a made-for-TV ending of the Iraq war, the film shows why we need an editorial system that can still vet stories, not just pass them on. For outlets like Gawker, the bottom line may be “all about the story, and it doesn’t matter where the story comes from,” as Gizmodo’s Brian Lam said after a screening at Gawker HQ last night. That may mean eye-grabbing headlines (Nick Denton says in the film that no one wants to read the Times). But as the Judith Miller fiasco famously taught us, focusing on stories over sources is precisely how journalism can get us into trouble, and precisely why people like Judith Miller represent an even more formidable threat to the Times than the Internet: without reptutation, accurate information, and good reporting – no matter how hard the story is to get or to tell – no one would be worried about losing the Times to begin with.

David Carr gets to defend these journalistic rigors when he pays a reporting visit to the offices of VICE (the publishers of Motherboard), and announces that he’s not going to get fed a line about the relevance of “new media.” “I don’t do corporate portraiture,” he tells VICE’s Shane Smith. Smith says he doesn’t do stories on surfing in Africa, implying that’s what the Times does, preferring instead to show cannibalism and war-torn waste lands. (VICE, it’s worth noting, produces a number of videos about snowboarding and skateboarding.) But brutal images captured in travel documentaries don’t count as news gathering, Carr reminds him, with a bit of old media brutality.

“Before you ever went [to Africa], we had reporters there reporting genocide after genocide. So just because you put on a [expletive] safari helmet and look at some poop, that doesn’t give you the right to insult what we do.”

Pause, as he stares down the VICE men. “So continue.” Tape recorder back on.

As good a badass character as Rossi has found in Carr, he’s certainly an unlikely spokesperson for the Times, which in spite of its peerless status, can still be accused of stodginess, of arrogance, of obnoxious trend stories. But the triumphalism of new media mavens like Jeff Jarvis, Arianna Huffington and Michael Wolff ultimately rings hollow against an even more compelling argument by Carr, the one he makes, remarkably, without even opening his mouth. At an old vs. new media debate, he shows the audience a print out of the front page of Wolff’s kaleidoscopic Newser.com. Then he picks up another copy, this time with the stories aggregated from “old media” torn out of the page. It’s full of holes, like some stale Swiss cheese.

The debate is much more complicated than that of course – new media and old media exist in a growing symbiosis – and much more interesting too. With David Carr as the film’s Ulysses, we get a neat metaphor for the messiness and interestingness of the moment: a baby boomer with a complicated past who manages to keep one foot in social media and the other in the kind of media still made by calling people up on the telephone. Here’s a man who is capable of covering not just what’s going on inside the newsroom or on the web, but covering the newsroom and the web itself. “The media equation,” as David Carr’s column calls it, is a messy and tough and sometimes dull-sounding story. But it’s a mess we’re all in, and no matter how unsolvable it can seem, in the hands of good journalism, it can make for fascinating reading, and watching.

In his review in the New York Times today, Michael Kinsley calls Page One, the documentary about the New York Times, “a mess.” He’s right, but not in the way he thinks it is.

This is a movie about the news industry: of course it’s messy. Director Andrew Rossi leads his audience across the wasted media landscape, with stops along the way, writes Kinsley, at “WikiLeaks; the Pentagon Papers; more WikiLeaks; the survival issue; Gay Talese and his famous book on The Times, ‘The Kingdom and the Power;’ Comcast’s purchase of NBC Universal; the impact of Twitter; the danger of not sending reporters on trips with the president; how ABC has had to lay off 400 people.”

This is a movie about the news industry: of course it’s messy. Director Andrew Rossi leads his audience across the wasted media landscape, with stops along the way, writes Kinsley, at “WikiLeaks; the Pentagon Papers; more WikiLeaks; the survival issue; Gay Talese and his famous book on The Times, ‘The Kingdom and the Power;’ Comcast’s purchase of NBC Universal; the impact of Twitter; the danger of not sending reporters on trips with the president; how ABC has had to lay off 400 people.”Apart from the messiness of the topic itself, there’s something nice about a sprawling approach, especially when our stories so often come in the form of Tweets, updates and headlines designed to be clicked on. It’s satisfying to see a fly-on-the-wall account of the business (and one of its epicenters) at a moment when transparency is king, but it’s also nice to be reminded about how good stories can be told. It can be hard to remember in the chaotic ecology of the Internet, where we follow links down their rabbit holes towards not wisdom, not opinion, not reporting – but information that’s crowd-sourced, aggregated, liked, and thus given a stamp of “relevant,” “important.”

By Kinsley’s account, the movie, with its impressionistic, rambling portrait of the news business, sounds a lot like the Internet too, born of a style that “keeps things moving but requires some discipline.” Discipline is what serious journalism has, and this, he’s clear, is not it: “It flits from topic to topic, character to character, explaining almost nothing.”

But the movie is a portrait of chaos, and a compelling one at that. It’s not a newspaper article or a well-structured op-ed. It’s a testament to the sort of journalism that still matters, that still separates Page One from the Internet’s homepages. It’s proof that in whatever medium you’re working – and there are a lot to choose from now – stories matter, and so do their sources and their subtleties. “Page One” may explain almost nothing, but some things aren’t so easily explained. Some times they have to be seen, and thought about, and discussed.

Kinsley’s bitter assessment then serves as proof of precisely the kind of journalism that the movie documents. In the interest of avoiding a “conflict of interest,” here’s the Times striving for as much distance as it can on a documentary about its own newsroom. Kinsley (who works for Bloomberg) goes out of his way at the start to indicate there is no conflict here, which was presumably why he was asked to write it (despite not being a film critic at all) and why he sounds nearly indignant at the film’s emphasis on “a media columnist and reporter named David Carr,” who is guilty, apparently, of loving the Times.

Given all of its (defensive) sense of self-importance – one stoked now more than ever, by, for instance, what some indignant Times partisans in the movie call “stupid” rumors of the newspaper’s demise – it’s not surprising to see a writer in the Times flaunting the paper’s concerns over integrity, like the righteous golden boy that new media expects it to be. “The Times deserves a better movie,” writes Kinsey imperiously, before adding the exortation, “and so do you. See ‘His Girl Friday’ again.”

Nerves have been touched clearly, and Kinsley’s review is only further proof, again, of a point that the movie is trying to make: if it’s not fighting for its life, good, level-headed journalism is on a mission to prove itself worthy in the heady, loud age of the Internet.

Carr is a fantastic spokesperson for that mission (and for the paper in general) and for the meta concerns at the heart of a shrinking newsroom. “There was just this sort of decades of organizational hubris about, you know, our own excellence and our own dominance,” he tells the camera early on in the film. “And then in a matter of like 18 months, all of a sudden…everybody started like asking a question: could The New York Times, like, go out of business?”

In an effort to remain balanced and fair and critical, papers like the Times aren’t competing against a “new media” boogeyman. They’re already deeply and often smartly embedded in the Internet themselves, and that’s where things get messy. Struggling with new modes of reporting, Internet economics and increasingly fuzzy lines between the demands of advertising and the demands of editorial, the corporate structure of news – “the muscles of the institution,” as Carr calls them – presents its own challenges to the newsroom. Through the collapse of the Tribune company and the Comcast NBC merger, the film points at these challenges, without making any claims. The story is still developing, is the point, and it’s complicated.

If “Page One” is ultimately a meditation on a shift between old and new technologies (Twitter and the iPad both make prominent, almost ominous appearances), what’s mostly missing is the story about the message that those technologies carry. When the tools effect the content, they’re really inseparable. But the content – what goes on Page One – gets little screen time here.

Still, in one of the film’s best scenes, when Times’ editors argue over whether to cover a made-for-TV ending of the Iraq war, the film shows why we need an editorial system that can still vet stories, not just pass them on. For outlets like Gawker, the bottom line may be “all about the story, and it doesn’t matter where the story comes from,” as Gizmodo’s Brian Lam said after a screening at Gawker HQ last night. That may mean eye-grabbing headlines (Nick Denton says in the film that no one wants to read the Times). But as the Judith Miller fiasco famously taught us, focusing on stories over sources is precisely how journalism can get us into trouble, and precisely why people like Judith Miller represent an even more formidable threat to the Times than the Internet: without reptutation, accurate information, and good reporting – no matter how hard the story is to get or to tell – no one would be worried about losing the Times to begin with.

David Carr gets to defend these journalistic rigors when he pays a reporting visit to the offices of VICE (the publishers of Motherboard), and announces that he’s not going to get fed a line about the relevance of “new media.” “I don’t do corporate portraiture,” he tells VICE’s Shane Smith. Smith says he doesn’t do stories on surfing in Africa, implying that’s what the Times does, preferring instead to show cannibalism and war-torn waste lands. (VICE, it’s worth noting, produces a number of videos about snowboarding and skateboarding.) But brutal images captured in travel documentaries don’t count as news gathering, Carr reminds him, with a bit of old media brutality.

“Before you ever went [to Africa], we had reporters there reporting genocide after genocide. So just because you put on a [expletive] safari helmet and look at some poop, that doesn’t give you the right to insult what we do.”

Pause, as he stares down the VICE men. “So continue.” Tape recorder back on.

As good a badass character as Rossi has found in Carr, he’s certainly an unlikely spokesperson for the Times, which in spite of its peerless status, can still be accused of stodginess, of arrogance, of obnoxious trend stories. But the triumphalism of new media mavens like Jeff Jarvis, Arianna Huffington and Michael Wolff ultimately rings hollow against an even more compelling argument by Carr, the one he makes, remarkably, without even opening his mouth. At an old vs. new media debate, he shows the audience a print out of the front page of Wolff’s kaleidoscopic Newser.com. Then he picks up another copy, this time with the stories aggregated from “old media” torn out of the page. It’s full of holes, like some stale Swiss cheese.

The debate is much more complicated than that of course – new media and old media exist in a growing symbiosis – and much more interesting too. With David Carr as the film’s Ulysses, we get a neat metaphor for the messiness and interestingness of the moment: a baby boomer with a complicated past who manages to keep one foot in social media and the other in the kind of media still made by calling people up on the telephone. Here’s a man who is capable of covering not just what’s going on inside the newsroom or on the web, but covering the newsroom and the web itself. “The media equation,” as David Carr’s column calls it, is a messy and tough and sometimes dull-sounding story. But it’s a mess we’re all in, and no matter how unsolvable it can seem, in the hands of good journalism, it can make for fascinating reading, and watching.

Comments

Post a Comment